Abstract Data Types and Objects

Two fundamental approaches to data abstraction

There are three main methods of representing data which developers are likely to encounter: abstract data types, algebraic data types, and objects. Abstract data types (frequently abbreviated “ADTs”) are likely familiar to developers with a computer science background, and algebraic data types (unfortunately also abbreviated “ADTs”) are likely familiar to developers with a functional programming background. Objects are a concept that most developers are extremely familiar with on a practical level, but many struggle to precisely define. These three approaches each have distinct tradeoffs, and familiarity with their characteristics can enable developers to choose the most advantageous approach for a given problem. This post will introduce and compare two of these, abstract data types and objects. I do the same for algebraic data types in the sequel to this post, here. Example code will be written in JavaScript using the Flow type system.

This post is heavily based on what may be my favorite paper, “On Understanding Data Abstraction, Revisited” by William Cook. I have tried to pull out and present the concepts which are most likely to be relevant to the average JavaScript developer while omitting more abstract mathematical concerns, but for those who are motivated, I highly recommend reading the original paper and its companion essay.

Abstract data types: representing data opaquely

An abstract data type is a model for data consisting of values and operations, whose concrete structure is hidden. For example, a

Set abstract data type is defined as having operations like add, remove, and has. Each of these operations mutates or returns a Set value, but the means by which they do so, or by which a Set is represented, is hidden from consumers of the Set type. To be strictly correct, the word “model” is an operative part of this definition: an abstract data type is an idea, describing a data type that could be represented in different languages. Colloquially, it’s common to use the term “abstract data type” to refer both to the formal definition of the data type as well as to concrete implementations of it. I will use the colloquial definition, and refer to software components which hide their internal structure as abstract data types.

There are several abstract data types built into the JavaScript language:

Set, Map, and Array are good examples. Developers have the ability to create and manipulate these, but are not able to access, modify, or extend their underlying representations. (Assuming we are limited by the constraints of good sense and decency and don’t try to modify the prototypes of things that we shouldn’t.) This leads to a fundamental tradeoff which characterizes abstract data types: by making the implementation of the data opaque, we have gained modularity at the expense of extensibility.Objects: representing data through composable interfaces

Cook’s definition of objects and object-oriented software discards many things which are normally considered essential to the paradigm, such as classes, mutable state, and inheritance. His definition instead centers on a total dedication to encapsulation. This is the definition that we will use here: a system is properly built out of objects if every function or method in the system only has access to the internals of a single abstraction. A method on the

Foo class can only access the internal structure of Foo; any interaction with another object must be done through that other object’s interface. Functions which do not exist as methods on a class cannot access the internals of any object, and can only interact with objects through those object’s published interface. Language features which allow you to break an object’s encapsulation, such as using instanceof to figure out what concrete type of object is providing the interface being used, are completely disallowed.

This definition is clearly based on established object-oriented principles: “maintain encapsulation” and “code to an interface, not an implementation” are well-known sayings among object-oriented programmers. This definition is much stricter, though, and a great deal of code which is often referred to as “object oriented” would be more accurately described as “imperative, using classes” under this definition. Cook calls the guiding principle of his object-oriented programming “autognosis”, meaning “only having knowledge of one’s self”. As we’ll see in the next section, implementations which follow autognosis have a very different set of costs and benefits than ones which do not.

An abstract data type representation of a set

To make the nature of and distinction between abstract data types and objects more concrete, we’ll implement the same data structure in each. The structure in question will be a set holding numbers.

The easiest implementation of this set as an abstract data type (though not the most efficient) is as a sorted array. This is what we’ll use here. We’ll provide five functions which operate on these sets:

empty will create an empty set, add will add an item to a set, isEmpty will tell us whether a set is empty, has will tell us whether a set contains a given item, and union will merge two sets together. Here is our implementation:export opaque type NumberSet = Array<number>;

export function empty() : NumberSet {

return [];

}

export function add(n: number, set: NumberSet) : NumberSet {

let i = 0;

while(n < set[i] && i < set.length) { i++; }

if (set[i] === n) return set;

return set.slice(0, i).concat(n).concat(set.slice(i)); }

export function isEmpty(set: NumberSet) : boolean {

return set.length === 0;

}

export function has(n: number, set: NumberSet) : boolean {

for (const num of set) {

if (num === n) return true;

}

return false; }

export function union(

set1: NumberSet,

set2: NumberSet) : NumberSet {

const newSet = [];

let i = 0,

j = 0;

while (true) {

if (i === set1.length) return newSet.concat(set2.slice(j));

if (i === set2.length) return newSet.concat(set1.slice(i));

if (set1[i] === set2[j]) {

newSet.push(set1[i]);

i++;

j++;

} else if (set1[i] < set2[j]) {

newSet.push(set1[i]);

i++;

} else {

newSet.push(set2[j]);

j++;

}

}

return newSet; // unnecessary return; make typechecker happy }

A few things to note about this implementation:

- We use the

opaquekeyword when exporting the definition of theNumberSettype. This means that Flow will signal an error if code outside of this file tries to access the underlying representation ofNumberSetas an array; all creation and manipulation of theNumberSettype must be done through the exported methods. In this way we ensure that our data type really is abstract. - Our

NumberSettype is immutable; ourinsertandunionfunctions return a newNumberSetwithout modifying their inputs. This shows that abstract data types are compatible with purity and functional programming, despite the fact that the ones built into JavaScript are mutable. - Our

emptyandisEmptyfunctions run in constant time; our other functions run in linear time on the size of the set. A less naive implementation could reduce these to logarithmic time. - Our

unionfunction absolutely does not respect autognosis: it takes in two different sets, and operates on the internals of both, iterating through them as arrays. This solution is not object-oriented, by the definition we’re using.

An object implementation of a set

To implement

NumberSet with objects, we first need an interface for the objects that we’ll be working with. Here is this interface:export interface NumberSetI {

add(number): NumberSetI;

isEmpty(): boolean;

has(number): boolean;

union(NumberSetI): NumberSetI;

}

This interface has four of the five functions which we implemented for our abstract data type. Rather than providing a way to get an empty set as a method on our interface, we’ll create a class for empty sets:

export class Empty implements NumberSetI {

add(n: number) { /* ??? */ }

isEmpty() { return true; }

has(n: number) { return false; }

union(set: NumberSetI) { return set; }

}

The implementation of most of these methods is obvious. An empty set always returns

true when asked if it is empty, and false when asked if it contains a given item. The union of an empty set and another set is just this other set. Adding to an empty set is more puzzling, however. By definition, an empty set doesn’t hold anything, so Empty shouldn’t have any logic around holding items. We’ll address this by making a new class which is responsible for adding items to a set, which Empty can return for this purpose:class Insert implements NumberSetI {

n: number;

set: NumberSetI;

constructor(n: number, set: NumberSetI) {

this.n = n;

this.set = set;

}

add(n: number) { return new Insert(n, this); }

isEmpty() { return false; }

has(n: number) { return n === this.n || this.set.has(n); }

union(set: NumberSetI) { /* ???? */ }

}

The

Insert set is constructed by providing a number and another set, and is responsible for representing that set with the given number added to it. Insert only takes responsibility for this one number; if asked whether it contains a different number with has, Insert will pass responsibility for determining this off to its contained set. We can use this class to complete our implementation of Empty, with a trivial implementation of add:add(n: number) { return new Insert(number, this); }

We’ll implement the

union method of Insert in a similar way. Taking the union of two sets is a very different responsibility than inserting a number into a set, so we’ll make a separate class for it:class Union implements NumberSetI {

set1: NumberSetI;

set2: NumberSetI;

constructor(set1: NumberSetI, set2: NumberSetI) {

this.set1 = set1;

this.set2 = set2;

}

add(n: number) { return new Insert(n, this); }

isEmpty() { return this.set1.isEmpty() && this.set2.isEmpty(); }

has(n: number) { return this.set1.has(n) || this.set2.has(n); }

union(set: NumberSetI) { return new Union(this, set); }

}

With this, we can implement

union on Insert asunion(set: NumberSetI) { return new Union(this, set); }

Compare our

Union object to the union implementation of our abstract data type. That implementation combined two sets by being aware of each of their internal structures. This one implements its has and isEmpty functions by delegating responsibility to each of the sets which it wraps. It interacts with these other sets through their public NumberSetI interface, without knowing what concrete class is involved. This means that our Union class respects autognosis.

Just as with our abstract data type implementation, all of our data here is immutable. The

add and union methods don’t modify the sets they’re called on, but rather return a new set. While people usually think of object-oriented programming as being based on mutability, objects can be very useful without any mutable state.Tradeoffs between abstract data types and objects

Abstract data types and objects have radically different characteristics, both in their implementations and in their usage in a larger system.

Looking first at these two implementations in isolation, we can see that their performance characteristics are radically different. For our abstract data type,

isEmpty was a constant time operation, and the runtime of union, add and has were based on the number of items in the set. For our object implementation, union and add are constant time operations, while the runtime of has and isEmpty are based on the total number of methods that have been called on our set. In general, many performance optimizations are based on reducing some complex or redundant structure to an equivalent but smaller case. When we follow autognosis, this approach is not available, because we don’t get to inspect the concrete structure that we’ve created. For example, when we take the union of two sets in the abstract data type implementation we eliminate any duplicate entries. If we take the union of the same sets over and over, our set will not grow, and later calls to has will not be any slower. In our object implementation, Union has no way to know whether the sets its combining overlap, and so can’t perform any kind of simplification. Calling union repeatedly on the same sets will result in more and more Union nodes being added, and later calls to has on this set being slower.

There is a justification for this cost: object implementations can be easily extended in ways that are impossible for abstract data types. The internal structure of an abstract data type determines and limits what data it can represent, but objects can represent anything for which we can define their interface methods. For instance, our abstract data type implementation has no way to represent infinite sets, but our object implementation can represent them easily:

export class Everything implements NumberSetI {

add(n: number) { return this; }

isEmpty() { return false; }

has(n: number) { return true; }

union(set: NumberSetI) { return this; }

}

export class Even implements NumberSetI {

add(n: number) { return new Insert(n, this); }

isEmpty() { return false; }

has(n: number) { return n % 2 === 0; }

union(set: NumberSetI) { return new Union(this, set); }

}

Everything is the set which contains all numbers, while Even contains every even integer. Their implementations are trivial, and they can be used with all of our existing sets. If the sets we’ve written so far were published as a library, callers of the library would be free to implement their own sets, without needing anything from our library but the interface definition. The set of all prime numbers, the set of all numbers in a range, or any other set you’d like could be written and would interoperate with each other.

Objects are clearly superior to abstract data types when it comes to adding new representations, but this doesn’t mean that they are more extensible in every way. Consider adding a

smallestIntegerAbove function, which takes a number, and returns the smallest integer which is contained in the set that is larger than the provided number, or null if no such integer exists. Adding this to the abstract data type requires adding one additional function:function smallestIntegerAbove(

n: number,

set: NumberSet) : number | null {

for (const num of set) {

if (num > n) return num;

}

return null; }

To add this method to our object implementation, though, we’d have to modify every

NumberSetI instance that we’ve implemented. Empty, Insert, Union, Everything and Odd will all have different implementations of smallestIntegerAbove. Worse, imagine that we had published both of these set implementations on npm. Adding a new function to the abstract data type implementation would be a minor change; our users could upgrade and just ignore the new function if they don’t want to use it. For the object implementation, extending the interface expected from objects would be a breaking change. Upgrading would require users to write additional code in order to stay compatible with other set implementations.

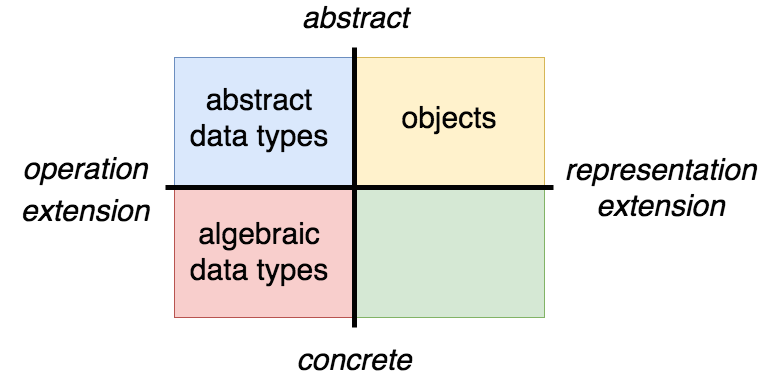

Abstract data types are thus easily extensible in terms of operations, but not in terms of representations, while objects are easily extensible in terms of representations, but not in terms of operations. This tradeoff of operational extensibility versus representational extensibility is known as “the expression problem”. There are solutions to this problem which enable both kinds of extensibility for objects in a modular way, but they are much more involved than the easy representational extensibility which we have right now.

Abstract data types and objects both provide data abstraction. This means that, from the perspective of a user consuming them, data is defined in terms of “what can be done with this data” rather than “what structure this data has.” For abstract data types, this abstraction is achieved by implementing a structure for data internally, and hiding this structure from users. For objects, no consistent structure exists, and data is represented as the composition of the behaviors which appear on the object’s interface. The individual objects which are combined to form a single data structure are as isolated from each other as the implementations of abstract data types are from the users who consume these types. Techniques which break the abstraction provided by object an object’s interface, such as the use of

instanceof, are thus strictly forbidden.

This fundamental distinction leads to a number of tradeoffs. Abstract data types are much easier to optimize than objects, but are impossible to extend without access to their internal implementation. Objects may be freely extended by creating additional representations which conform to the object’s published interface, even by users who are consuming the objects from a library. The use of concrete structures inside of abstract data types makes extending these structures with additional representations difficult, but a library author has a great deal of freedom to add new operations. In contrast, despite the ease with which objects may be extended representationally, adding new operations to them tends to require sweeping changes.

The two concepts are complementary, and one’s strength tends to be the other’s weakness. When you need data abstraction, knowing their tradeoffs is immensely important for choosing the appropriate tool for a given situation.

The capabilities of these two are vast, but they aren’t the only approaches to representing data. Algebraic data types are a third option, which represent data as a composable, concrete structure. I introduce them and contrast them with abstract data types and objects here.

No comments:

Post a Comment